During half term, twenty-four A2 (Upper Sixth) pupils swapped the classroom for the cradle of the Renaissance on an Art, History of Art and Photography trip to Italy led by Head of Art Doug Knight, Head of History of Art Sarah Thomas, and Helen Dean, Teacher of Art.

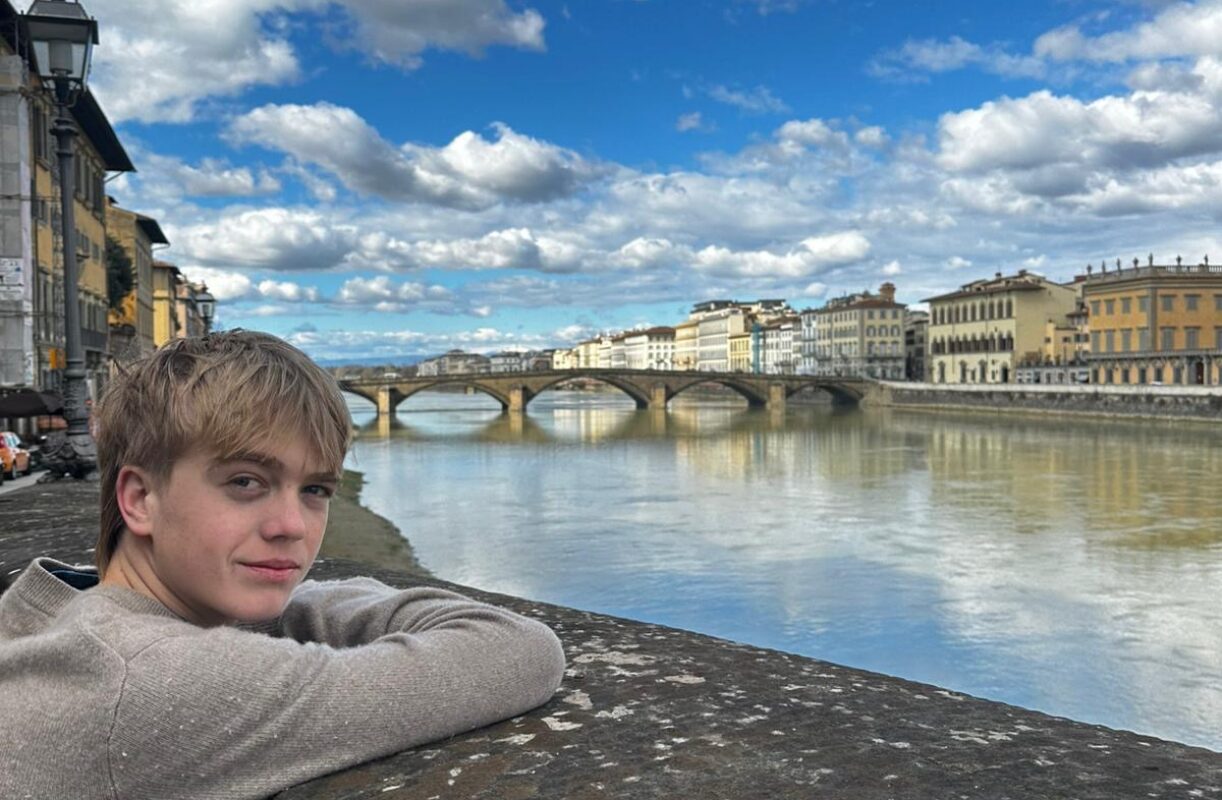

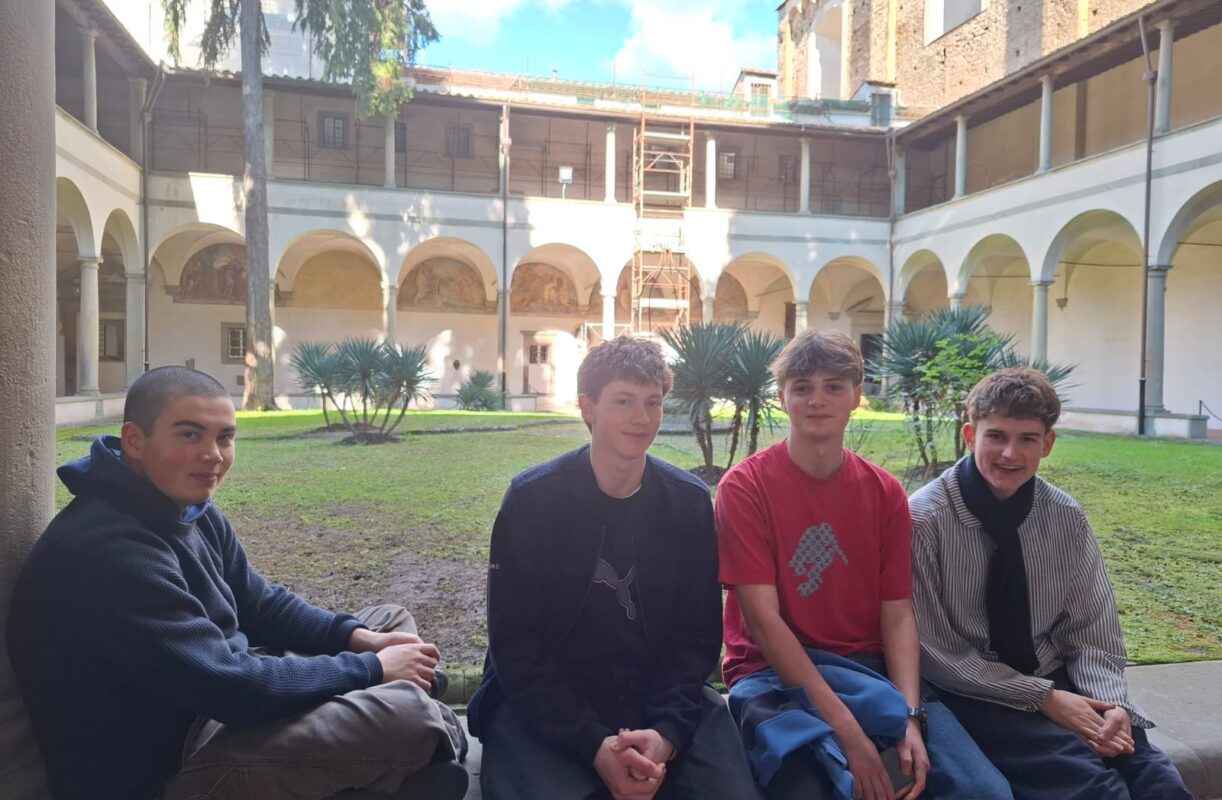

The group began with three nights in Florence, where pupils enjoyed some of the city’s most celebrated masterpieces. Highlights included a visit to the Uffizi Gallery, as well as a climb up Brunelleschi’s Duomo to take in the frescoes and sweeping views across Florence’s rooftops. After exploring the Brancacci Chapel, pupils took the walk up to San Miniato al Monte, rewarded with a panoramic perspective of the city that has inspired artists for centuries.

From Florence, they travelled south on a high-speed train to Rome, heading straight into the heart of ancient and Renaissance history. The group visited the Pantheon before making their way to the Vatican later that day, joining the crowds through the museums to reach the Sistine Chapel.

The final day in Rome offered time to explore more of the city’s artistic riches, including the impressive Villa Farnesina, alongside other significant sites across the capital.

The packed itinerary ensured everyone made the most of every moment, inspiring the young artists and photographers for the remainder of their course while giving art historians the invaluable opportunity to view studied works and artefacts with their own eyes.

Thank you to the staff who helped make the trip possible.