We use cookies on our website and you can manage these via your browser setting at any time. See our Cookie Policy to learn more.

To review our Privacy Policy, including our obligations under the General Data Protection Regulation, please see our Privacy Policy

PARENTS: Please note that you should allow cookies in order to log into the Parent Area. Further information

Pupil report: Award-winning author Beverley Naidoo visits Bryanston

Award-winning author Beverley Naidoo visited the School on Wednesday 11 March to talk to IB History, A3/A2 History and A3/A2 English pupils. Sixth form pupils from The Blandford School were also invited to attend.

Naidoo’s talk enabled us to learn more about an individual that was one of many that gave their life for the fight against apartheid and the brutal conditions that were faced by political prisoners.

talk enabled us to learn more about an individual that was one of many that gave their life for the fight against apartheid and the brutal conditions that were faced by political prisoners.

Naidoo writes about South Africa both in the non-fiction world and through fictional stories. Her first book Journey to Jo’burg (1985) was banned in South Africa, a result of half the royalties being given to the British Defence and Aid Fund (subsequently the Canon Collins Trust), an organisation that supported the families of political prisoners.

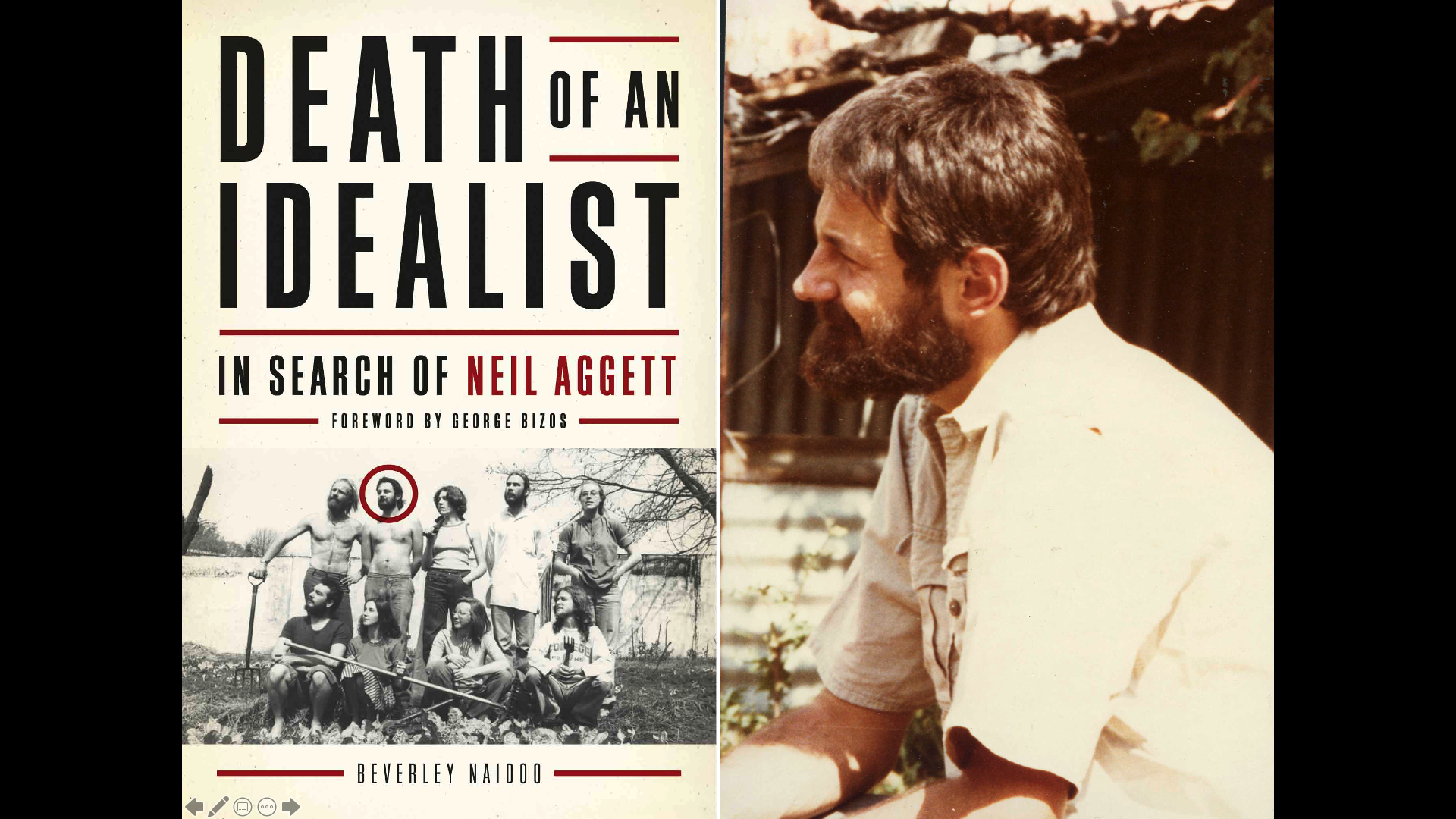

During the visit, Beverley mentioned how she wanted to remain in South Africa but was exiled after she was put in solitary confinement, and her brother serving a two-year prison sentence. During her talk at Bryanston she told us of the story enclosed in her renowned non-fiction book Death of an Idealist. She told us a biography about her cousin’s son Neil Aggett, a medical doctor whom the security police claimed had hung himself in his cell after being imprisoned for fighting against apartheid.

Aggett was born in Kenya, growing up during the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960). Aggett’s father was a settler who assisted the British police force, trying to prevent the independence of the Mau Maus. When independence was established in Kenya, Aggett’s father decided that it was time to uproot and move to South Africa. Here, Aggett was developing a sense of anti-apartheid as he grew up, refusing to be conscripted at the age of 18 years. Conflict between him and his father arose, writing to both his parents that he couldn’t be complicit to the apartheid policy.

Beverley Naidoo talked to us about how he experienced a sense of needing to be on the right side of history, with his work with unions (being appointed as an unpaid organiser of the Transvaal Food and Canning Workers' Union) as Naidoo explained this was where the driving resistance to apartheid took place inside the country. He worked weekends as a doctor to fund his trade union work, serving in black hospitals in Umtata, Eastern Cape and Tembisa in Transvaal. Naidoo showed images of John Vorster Square (a police station) with its intimidating height and windows, where Aggett supposedly committed suicide after he was arrested in 1982. Naidoo highlighted the suspicious nature of suicide as this was a common excuse the police used to cover up the deaths that were committed in police custody. He was among many political detainees, like Ahmed Timol, to die in this circumstance. Aggett’s contribution to fighting apartheid was particularly striking with the fact that there were 15,000 marchers, mainly black trade unionists, at his funeral. Black Sash protestors held up ‘death by detention’ posters outside, highlighting his contribution further.

At Aggett’s inquest in 1982, the family's lawyers argued for a finding of ‘induced suicide’ and a testimony given by fellow detainee Maurice Smithers, in a note passed on to Helen Suzman, details the humiliation that Aggett had undergone. George Bizos, the same lawyer that represented Nelson Mandela at the Rivonia Trial (1964) and Steve Biko, represented Neil Aggett, where it was declared there was ‘no-one to blame’ – also another common phrase used to explain these types of deaths. At the TRC, it was ruled that Major Arthur Cronwright and Lieutenant Stephan Whitehead were responsible for Aggett’s death, but neither came forward to relay their story or ask for amnesty. Naidoo pointed out that although the Truth and Reconciliation Commission should be accredited for how it did unify and bring truth to cases similar, for testimonies like Aggett’s, the National Prosecuting Authority had failed to follow up for very many years on almost all 300 cases where amnesty wasn't granted. Similarly, when the Aggett inquest was announced to be reopened, Naidoo pointed out how the chief interrogator at Neil Aggett’s induced suicide case died conveniently in the same week.

Naidoo’s talk reminded me of the way that resistance had come together and unified people, despite being told that they were different because of their race or gender.

By Eliza H